You may be wondering what “backslopping” is.

Let’s say you’re making kombucha, and you add a few tablespoons of kombucha from a previous batch to start the fermentation. And how about pickles? Some brine is taken from a previous batch and added to the fresh brine.

Backslopping is the term used for the action of benefiting from a “starter” in a new ferment. That is, backslopping occurs when the food to be fermented gets a boost of beneficial microbes by adding a dose of a previous batch of that same ferment.

This helps us get the new ferment going.

Why Is Backslopping Beneficial When Fermenting?

Backslopping refers to the practice of taking a small portion of a ferment and saving it to start the next batch.

It is something that, for example, we can do with sauerkraut or other ferments by taking two to three tablespoons of the ferment to cultivate the next batch. But why do this?

This ancient practice is very helpful as it helps drop the pH of the ferment faster. Most fermented foods are acidic, and the reason is that acidity protects. The low pH of the ferment protects it from possible contamination by pathogens, i.e., unwanted microbes. If, for example, fermented juice is added to the next batch that hasn’t started to ferment yet, it gives the new batch microbial life and makes it more acidic, which lowers the pH of the ferment more quickly and keeps it from getting contaminated by molds and fungi.

If there is a pathogen, an unwanted microbe, the chance that it can take over goes down considerably since there is already a population of good bacteria. By good bacteria, we mean the ones that we want to flourish so that we get the desired result.

Backslopping is also important because it makes it possible for good bacteria to flourish. In other words, we are introducing an ecosystem that is already established. This is like telling a child, “Go this way to get to your destination.” That is what backslopping does with bacteria, it traces the route along which they must transform the ferment, protecting it from possible contamination. If good bacteria are added on day one, they will take over the fermentation process faster.

In other words, backslopping is taking a portion of the previous batch to start the next one, helping to lower the pH of the ferment and giving it protection, directing production, and introducing a healthy and already established ecosystem.

By backslopping, we are following a microbial lineage, creating a thread that connects every ferment we make. This is something that can be done not only with vegetable ferments but with any type of ferment. With milk kefir grains, the grains themselves are a way of backslopping, of following a microbial lineage between batches. From sourdough, some of the previous fermentation is left to follow the microbial lineage, that is, the thread that connects one fermentation to another through time. The containers used for fermentation provide backslopping if we do not wash them between fermentations—a healthy and established ecosystem of microbes already lives there. Another tool for backslopping are the wooden utensils that we use if we don’t wash them between fermentations, only letting them dry in sunlight.

The Fermentation Curve

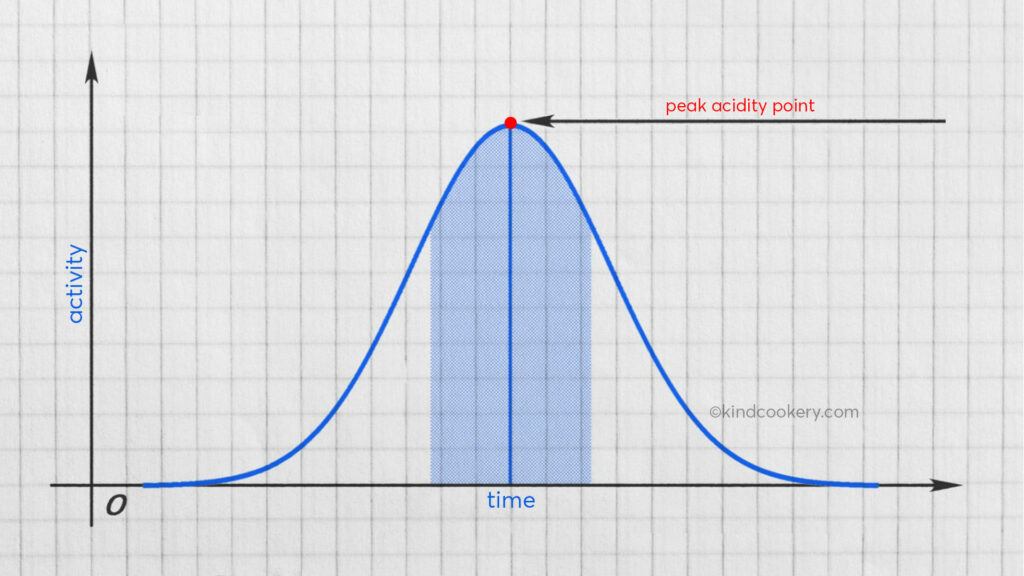

The fermentation curve is the timeline of the ferment. All fermented foods have a curve where two parameters are measured: activity and time.

At first, none of the fermented foods are very active. They all reach a peak of activity, then slow down. When they are at their most active, they are usually at their most acidic (since acidity is protective). At the peak of activity, we will see signs, such as bubbles, that there are many active microbes in the ferment. It is important to know that when a ferment reaches its highest level of acidity, it is likely to stay at that level and not go down.

We must keep in mind that the ferment evolves and changes over time. In other words, there are no rules in fermentation because, as the curve shows, the length of time it takes for a ferment to reach its peak and then drop depends on a number of variables, including what we are fermenting and the environment’s temperature, which in turn depends on the season, etc. So, if we ever want to sell fermented foods, it’s good to ferment for a whole year to see how this curve changes through the seasons. It’s possible that a sauerkraut takes longer in a cold season to reach its peak of activity than it does in a hot season, for instance.

The curve is valid for fermented foods and cultures, such as sourdough. We can’t use the food when its activity is going down, it has to be at its peak. Clabber, for example, is sour milk that we use as a culture to make cheese, and it usually reaches its peak of activity in 12 hours or up to 24 hours, at which point we can use it as a culture for cheese. Using an already fermented culture to start the new batch brings the pH of the new ferment down faster and you have a safer ferment with less chance of contamination. So backslopping, using a culture to create a microbial lineage through generations, makes the ferment safer.

Fermenting is an art, not a science with exact rules, as everything changes depending on the temperature, the ingredients, the type of culture, the type of ferment, and so on.

We could say that backslopping makes a safe path for all of our ferments.